Every Time We Say Goobye, or What I've Learned about Relocation

Published Street Roots, November 26, 2010

A lodger caught in the closure of the Royal Hotel

The Portland streets are not where you’d want to be living in December. Not with six inches of rainfall and the city wet two days out of every three.

According to Amanda Waldroupe’s report, “Time’s up at the West” (Street Roots, November 12), tenants at the West Hotel have been handed a 60-day eviction notice and a list of apartment buildings. When they say they fear ending up homeless, they have a pretty specific picture in mind. The hotel they are leaving at 127 NW 6th is a 100-year-old “walk-up” where 26 single-room occupancy (SRO) rooms share a community kitchen and baths in the hall. It may not be the Benson, but it’s warm and it’s dry.

To add to the misery, residents hear the term “relocation” bandied about by journalists, social workers and housing advocates. Whatever it is, they fear it may not apply to them.

For the past 14 years I’ve been up to my neck in relocation. Here’s what I’ve learned.

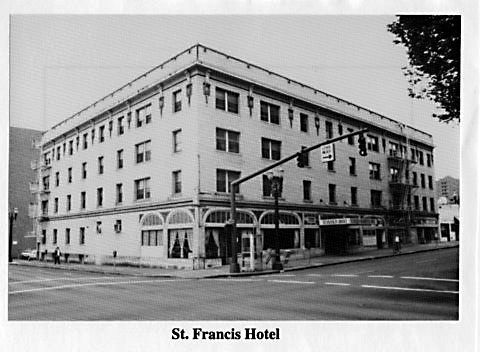

The old St. Francis was razed to create new – and more expensive – housing.

The Writer as Social Worker

The social work community was caught off guard when, in 1997, Roosevelt Plaza owners sent a letter to their tenants notifying them that, having reached the end of their initial 20-year contract with HUD, they planned to “opt out”of Section 8 housing. All 58 tenants would have to leave.

Northwest Pilot Project (NWPP), a social service agency that provides housing services for low-income seniors downtown, interceded in their behalf.

At that time, I had a contract with NWPP to write and produce their Affordable Housing Inventory, and had just sent the job to the printer when we heard the news. Susan Emmons, the director of NWPP, called me into her office and asked me to set up an office in the lobby of the Roosevelt and find those poor people replacement housing downtown.

I had a tenuous connection to social work: at Seattle Nightwatch in the early 1980s I helped people find shelter beds in the middle of the night; and for two Portland winters in the late ‘80s, I worked for the Low-Income Energy Assistance Program (LIEAP), doling out little bits of money so people could afford to turn on their heat. Mostly I was a writer and teacher of creative writing, and I took contracts, like the one with NWPP, to pay for the twin luxuries of writing whatever I pleased and of teaching at Marylhurst University as adjunct, untethered to faculty meetings.

For the Roosevelt Plaza relocation – another contract -- I had enormous help from several enthusiastic volunteers, including two Marylhurst students and one friend who left her job in television because she found more meaning in helping the poor. (Today she works as a paralegal specializing in appealing disability denials.) Volunteers helped people fill out rental applications – which can be voluminous if they’re for subsidized housing – drove tenants to look at apartments, listened to their indecision and their fears, and generally provided good cheer during the months it took to get everyone safely into new housing.

We learned so much. We learned the depth of grief and confusion felt by tenants cast out of a home where they’d been safe and comfortable, perhaps for 20 years, and who now feared abandonment or homelessness or something as simple as getting lost in an unfamiliar part of town.

We learned that all of our efforts – scouting for vacancies, providing cardboard boxes and high school students to help pack them, paying deposits and extra fees, hiring professional movers — can never entirely relieve the stress and anxiety of eviction.

We learned that no other apartment building duplicated the amenities of the Roosevelt – the central location, the proximity to Safeway, the gracious old building with a view of the Park Blocks. Still we did manage to secure units in two newly opened buildings – the Pearl Court on NW Kearney, and the Westshore on Southwest Pine – and in existing buildings throughout the city.

But the closely knit community of elderly Roosevelt tenants was scattered, and we learned to recognize and respect the longstanding network of friendship and assistance that had developed in that building. The elderly, in particular, cannot simply be uprooted after decades and sent off somewhere to live out the rest of their days among strangers. It seemed ironic that while so many busy wage-earners were regretting the loss of community in their own fragmented lives, developers and government had colluded to chip away at what little community the poor and the elderly had left. And so we also learned something about the history of housing policy in the city and in the nation.

In 1997, the Roosevelt Plaza was sold for conversion to condominiums.

A Little Background

In the glow of peace and prosperity following World War II, people of means packed up their Oldsmobiles and moved their young families to the suburbs, abandoning the cities to those too poor to make the move. With little upkeep or investment, U.S. cities went downhill. In Europe, by contrast, the middle class continued to prize their parks and fountains, opera houses and libraries: they stuck close by them, leaving the poor to squat on the fringes.

Attending to the needs of Portland’s downtown poor, many of them elderly, was an Episcopalian priest named Peter Paulson, who lined up 16 other churches in 1969 and started Northwest Pilot Project (NWPP). At first, the goal of the fledgling agency was simply to befriend. “We talked about how you approach a lonely person, how you establish relationship, how you understand your role in initiating that relationship,” recalled Paulson, whom I interviewed in 2001, four years before his death.

By 1974, Portland had nearly 6,000 units of rental housing available, including residential and transient hotels, to people living in poverty downtown. A community of 600 people lived in the vicinity of Lownsdale Square, a four-by-six-block area bounded by SW Main, Morrison, Front and Fourth.

A booklet published in 1971 by Portland State University’s Urban Studies Center offered this description: Lownsdale Square...is quietly busy even in relatively inclement weather. Older men play rummy on worn-smooth park tables next to the towering war monument, or checkers on a small wager to keep it interesting. Still others converse with an acquaintance or snooze or read a paper in a warm summer sun...”

When Mayor Neil Goldschmidt took office in 1973, he and a team of city planners projected their own vision on downtown: instead of spending money on the proposed Mt. Hood Freeway, the City would revitalize the downtown core, limiting auto parking and investing in new bus malls.

Goldschmidt’s timing was perfect: in 1974 Congress authorized the HUD project-based Section 8 program, which encouraged developers to upgrade existing buildings for use as safe, clean, low-income rental housing. In Portland, qualifying elderly and disabled tenants moved into these new projects, where they paid only one-third of their income for rent, while the federal government supplemented that modest contribution, thus making up the difference to landlords.

The first thing to understand is that the Section 8 program benefited businessmen, who were initially guaranteed by the federal government a generous “fair market” rent. These programs were meant to attract investors, and that is not done by low-balling profits: the feds ensured there was money to be made by housing the poor.

It worked in Portland: Developers invested in the downtown. The Admiral, the Oak, the Park Tower and the Roosevelt Plaza were just four of the many such buildings turned into Section 8 housing, always 100 percent occupied and generally with long waiting lists.

For Paulson and NWPP, revitalization was challenging. On the one hand, the new project-based Section 8 apartments were a godsend, insofar as they helped solve the problem of maintaining elderly clients in downtown rental housing. But with the city in a frenzy of improvement, and so many apartment buildings deemed not worth fixing up, NWPP staff was kept busy rescuing people whose lodgings fell to the wrecking ball.

“The first relocation we had was the Freeway Hotel up there on West Burnside,” recalled Paulson. “The building inspector and the fire department said it should be shut down. This was in ‘75 or ‘76.” Paulson estimated there were maybe 40 people in there, and his staff found most all of them a place to live. “One old Norwegian,” Paulson remembered, “refused to leave.”

Following the Freeway Hotel, Paulson and his staff moved people out of hotel after hotel downtown, like the Kenton and the Hatchie Rooms. They moved tenants from the Laurel Hotel when it was closed for code violations, and the Park Haviland when it was scheduled for remodeling. In 1986 the Governor Hotel was closed and 110 tenants evicted. When it finally re-opened, five years later, as a high-end hotel, the cost to rent a room for the night was equal to what the seniors had paid for a month.

In 1987, Paulson retired and Susan Emmons took over as director and began waging a long campaign to get the City to commit to preserving low-income housing. Having handled every major relocation in the city since the mid-seventies, NWPP staff understood what was happening to the poor as the city eliminated affordable housing. Emmons scored an early victory in 1988, when City Council, as part of the Central City Plan, promised to guarantee that 5,183 affordable rental units – an amount equal to 1978 housing stock – always be kept available downtown.

The old Lownsdale community was dealt a fatal blow when the General Services Administration decided to site the new federal courthouse there, requiring demolition of the Hamilton and Lownsdale Hotels, which together accounted for 194 rooms for very low-income people.

Exasperated, Emmons took a new position: it was no longer tenable to handle relocations without advocating for replacing the housing being lost. She waged a high-profile campaign that eventually turned into a class action law suit against the federal government, in which the City of Portland and Legal Aid fought alongside NWPP. Although the advocates lost the lawsuit, the federal government did make a commitment to fund housing to replace the two old hotels. It would be seven years, however, before all 194 new rental units were available.

Two years later, in 1994, NWPP began to publish the Downtown Portland Affordable Housing Inventory, an indispensable tool for social workers and a conspicuous public record, revised annually, of the city’s failure to keep their promise. The first edition I worked on was 1996, and we ran a list of the 17 buildings lost (rent increase, converted to other use, fire) in just two years: the Carmaleta, the Etheridge, the Hidwell, the New Ritz. The names roll off the tongue like a litany for the dead.

The Hotel Hamilton was torn down to make way for a new federal courthouse.

Meanwhile, city planners launched incentives and tax abatements to stimulate the development of downtown rental housing for middle class people. They called it the livable city initiative.

“The idea was to encourage people to move back downtown, people who had the money to shop at Nordstrom’s and eat at Jake’s,” says Emmons.

The 24-hour livable city idea sold so well, that a lot of empty nesters moved downtown to start life over in a condo. Of course, the hunt for likely condo conversions heated up an already competitive market, and a new crisis emerged: when those early HUD contracts began to expire, some owners decided it was a brilliant time to cash in on their investments. Finally, with real estate prices inflated, a new note began to be heard: “Downtown real estate is too costly for poor people. Maybe they should be living somewhere else.”

But NWPP staff never bought that argument.

“It seemed unfair to displace the historical downtown residents because city investment had created trendy neighborhoods,” says Emmons. “We also didn’t know where we were supposed to be moving people – other neighborhoods were gentrifying as well.”

A core belief at NWPP, going back to founder Peter Paulson, is that our lives are enriched by the elderly, with their particular wisdom and irreplaceable stories. And that, if the poor are no longer among us, we will be impoverished by the loss.

Former residents of the Roosevelt Plaza: Colette Turner, Joe Long and Olive Lacsamana

Back to the Roosevelt

The poignant spectacle of a mass eviction at the Roosevelt Plaza, including an adorable Italian nonagenarian who got her picture on the front page of the Oregonian, triggered a public reaction. The housing advocacy community (NWPP, Community Alliance of Tenants, and activists from a wide swatch of bureaus and agencies) paced off a weekly vigil for months in front of City Hall until finally, in September 1998, Council acted to prevent another of these tragedies. They passed a Housing Preservation Ordinance which provides a legal means for the City to intervene, either by buying a publicly-financed building at the time of owner opt-out, in order to preserve it as low-income housing, or by funding relocations so that the tenants get their deposits and moving costs paid. (Note: the West Hotel is not a publicly-financed building, so it does not qualify.)

This new ordinance was invoked in 2001, when Portland lost another 39 units of low-income housing. For 20 years, the Western Apartments, at 17 Southwest 2nd Avenue, had been operated as Section 8 housing available to elderly and disabled low-income tenants. When the owner notified HUD that he had no intention of continuing the program, a long chain of events was set in motion.

The City decided not to preserve it as Section 8 apartments, which was their option under the new Housing Preservation Ordinance. Instead, NWPP was asked to find new housing for all of the tenants and, again, I managed the relocation for them on contract, with the Portland Development Commission (PDC) paying relocation costs.

However, despite the expectation that tenants would be able to use the greater buying power of Section 8 vouchers to find one-bedroom apartments downtown, only 38% actually did. The others were housed, of course, but they either “paid” to stay downtown by stepping down to studios, or they went across the river. The lesson here is that 25 years of demolishing low-income properties had taken a toll, just as NWPP foresaw it would. The 2002 edition of the Inventory showed that Portland had nowhere near the 5,183 units guaranteed in the Central City Plan. In fact, it was short by 1,654 units!

In the Western relocation, volunteers again provided indispensable help. One, I remember, made hot coffee at 6:30 one morning and got everybody out of bed in time to make their appointments at the Housing Authority of Portland (HAP).

But, again, we saw the real costs that go unrecorded in any relocation budget, including an entire year of anxiety for tenants, as they waited to see what their fate would be. (As legally required, they had received a one-year notice.) For one tenant who suffered from schizophrenia, receiving his eviction letter triggered an episode of fear: he went off his medication, lost his caseworker and was left to fight his terror alone in his room.

Several other Western tenants were coping with HIV or AIDS, and the physical labor of moving was almost too much for them. One man stopped taking his medication in order to have the energy to move, only to become more sick.

The stresses of moving are incalculable. Two Western tenants died within a few weeks of relocation. There remains the haunting thought that the move was a factor: had she not been worried and distracted, might she have checked into the hospital earlier? Had he not been forced out of his haven, might he still be alive today?

When HAP announced plans to tear down the historic St. Francis, which they owned, NWPP vocally advocated for the preservation alternative. The building was attractive, with cast-stone cartouches (those ornamental ovals between top-floor windows) and elliptical-headed transoms over the storefronts. But HAP was determined to demolish and rebuild 100 low-income rental units as part of a three-block development to include the new Safeway. So in May, 2001, we began downtown Portland’s largest relocation to date. Because the hotel had 133 rooms, the task was split between me and housing guru Bobby Weinstock, the long-time NWPP staffer who had originally coached me in this work. We set up side-by-side offices in the old hotel and split the list of clients, each taking half.

Today, NWPP no longer does relocations. As director Susan Emmons points out, “We knew we could provide excellent service to the poor people being displaced, but we began to feel like we were part of the problem by even offering that service. We felt we were just enabling decision-makers to close buildings, because they figured NWPP could surely work out a relocation strategy. And, with the lack of available housing, it felt increasingly like an impossible task.”

So, after having pioneered Portland relocations, after having lessened the shock and the suffering of hundreds of people caught in the current of gentrification, after lobbying whomever they could think of –– sellers, buyers, the City, etc — to provide funds to make relocation seamless and at no cost to the tenant, NWPP decided, no more.

Today, they stick to their first and most urgent obligation, which is helping a lobby full of seniors who are homeless and have no place to go.

The Impact of National Policy

It should be clear that local history has been, to large extent, driven by national policy. It was the feds who established the Section 8 program in the first place, setting generous rent levels for developers who participated. Over the years, however, those rents have not always kept pace with open market rents, and this disparity has driven some of the smaller landlords out of the game.

Starting with Reagan, there has been a slow but steady dismantling of housing programs for the poor. Housing advocates pushed back in the ‘80s, managing to pass both the Uniform Relocation Assistance Act (URAA) and the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act. (Note how we already needed, by 1987, legislation to address the burgeoning homeless population).

But President Bush rammed policy back in Reagan’s direction with the so-called Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness, which identifies the chronically homeless, for whom it earmarks funds for services, without enough money to substantially increase housing. Instead, 10 inexpensive rooms at some existing building – say, Central City Concern — formerly available to anyone who met the low-income guidelines, are appropriated for the chronically homeless and a press release sent out crowing about the increase (by 10) in “new” housing under the plan. By 2008, there were 860 cities across the country covered by Ten-Year Plans to End Homelessness, a deception perpetrated by Bush-era HUD. Meanwhile, we have yet to address the root cause of homelessness, which is a shortage of low-income housing.

Of course it’s complicated, but it’s also just that simple: homelessness is tied to insufficient housing stock. Without memorizing all the acronyms, or how tax credit financing works, or the history of HUD programs, you can figure out something’s hugely wrong by just looking at all the people pushing shopping carts or carrying their belongings in plastic garbage bags, or shivering in wet sleeping bags in doorways. Today we have three times the number of people homeless as we did during the Great Depression. Roughly 3 million today, 1 million back then.

The Situation at the West

The 1987 URAA governs relocation and the need to provide compensation. Linked to federal highways legislation and supported by Senator Ted Kennedy, it was passed by Congress despite Reagan’s veto. The legislation updated a 1970 Act that provided for financial assistance for people displaced when the feds built highways across private land, condemning houses and businesses in the process.

The URAA establishes uniform policies to compensate people displaced by state and local government programs, and a parallel federal law (42 USC 4601) applies when projects are wholly or partially federally-funded trigger displacement. A good fact sheet, supplied by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, can be found online at http://www.fema.gov/pdf/government/grant/resources/hbf_ii_3.pdf

As Waldroupe’s Street Roots story verified, the owners did file a relocation plan with Oregon Housing and Community Services, as they were obliged to do when they applied for construction funds. However, Oregon, in the great government tradition of paperwork for paperwork’s sake, does not follow-up or enforce. It’s a loophole we citizens have to see closed.

In any event, the Macdonald Center should not be cast as the villain in this scenario, but rather as the uninitiated. When Fr. Richard Berg, C.S.C., then pastor at the Downtown Chapel, raised all those millions to build the new assisted living facility back in 1999, he was responding to his own sorrow at seeing so many elderly people dying alone in their skid row SRO hotels or on the street. The Macdonald Center, with 54 rooms, was the first assisted living facility in the nation to have 100 percent Medicaid beds. That means people scratching by on a $400 month Social Security check, say, can afford to live there, where they are fed, bathed, dressed and loved. It also means they should have enough good karma to carry them through the confusion at the West, a neighboring property they bought in hopes of providing housing much nicer than the existing old hotel.

Given the short time frame, tight rental market, unseasonable weather and acknowledged personal barriers to housing (that’s the euphemism signaling that someone may have a criminal record, poor credit, or a bad track record for staying on his meds), the most practical way to take care of West tenants at this point might be to negotiate a block of motel rooms for them to occupy until the new building is ready. And then bring them home.

The Boomerang Model

In the last couple of years, we’ve begun to see a new model: a HUD building sells to a new owner who then needs to “temporarily” put tenants out in order to sufficiently rehabilitate the property to qualify for a new HUD contract.

This is, of course, a good thing: it preserves low-income housing stock and a beautiful and historical old downtown building.

The bad thing is that the tenants are required to live through it.

In 2008, when REACH Community Development purchased the Admiral, at 910 SW Park, they approached NWPP to help them figure out this “boomerang” relocation, with the aim of providing, two years down the road, updated apartments for all the original tenants. Weinstock, on behalf of the agency, referred the project to me.

What we all learned from the experience – Admiral tenants, NWPP, REACH and we who actually did the relocation, myself and five volunteers – is that the boomerang relocation is even harder on the health and sanity of an elderly person than a one-way move. One individual died at the Admiral, and five others passed away, one in an apartment building and four in assisted living facilities, within months after they moved. Of course we can never know for sure what the outcome would have been had we never relocated, but it is painful to think that, in trying to make someone’s lodgings safer and more beautiful, we may shorten their life in the process.

To relocate a frail elderly person who has been in the same apartment for a couple of decades is like requiring a hospital patient to get up, disassemble their own hospital bed, pack the pieces in boxes, then report to the office for six hours of federal paperwork. Of course, that’s just the outbound move.

A new boomerang relocation is about to begin, at Chaucer Court, a lovely old historic building at 1019 SW 10th Avenue. NWPP housing counselors count maybe 30 of their own clients living there, and they worry for their safety and peace of mind. Weinstock, acting on behalf of the agency, referred the new owners to me, and we have been talking about how best to pull it off, with the least disruption to the lives of the tenants.

“This is not how we ever thought it would look,” says Susan Emmons, struck by the irony of having to move twice – to avoid having to move. The idea of the Housing Preservation Ordinance, for which we all lobbied back in the nineties, was to not dislodge or disturb someone who is frail and frightened, possibly mentally ill or in a wheelchair or blind.

And this, of course, is not to mention the challenge of finding alternative temporary housing, even if only for six months or a year.

“The federal government refuses to acknowledge that mass homelessness is what it is — the absence of affordable housing.”

That’s a quote from WRAP, the Western Regional Advocacy Project, but it might have been spoken by Emmons or any other housing activist who knows you can’t get a cheap apartment downtown anymore, who grieves to see the homeless population continue to swell, and who recognizes the so-called “Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness” as the shell game that it is.

“Any strategy to end homelessness in Portland has to include a net gain of housing affordable to the poorest people in our community,” Emmons points out, stating the matter so simply that surely everyone can understand.

“One new building with 140 units will not do it. We need 10,000 apartments for families and individuals at 30 percent of MFI or less,” she estimates. “MFI” is HUD-speak for people whose income is only 30 percent of median for this area. And her calculation that we need 10,000 apartments is not made casually, but the result of working the arithmetic every day for the last 24 years that she’s been directing the agency.

Ten thousand units considers not just downtown, which is the area for which NWPP has responsibility, but refers to Portland as a whole. And if we do not create this housing, we can expect to see the numbers of people on the streets continue to grow.

In a sense, tenants at both the Chaucer Court and the West Hotel are both casualties in a failed national housing policy.

Yet Chaucer Court will be preserved as subsidized housing, and the tenants well taken care of during their upcoming moves.

But we are puzzled and saddened by the West Hotel, where the plan was to evict poor people in order to build new housing for (other) poor people who, as someone once calculated, will always be among us. We hope the owners can come up with a creative and compassionate solution because, come December, there’s going to be a lot more rain.

Roosevelt Plaza's empty lobby