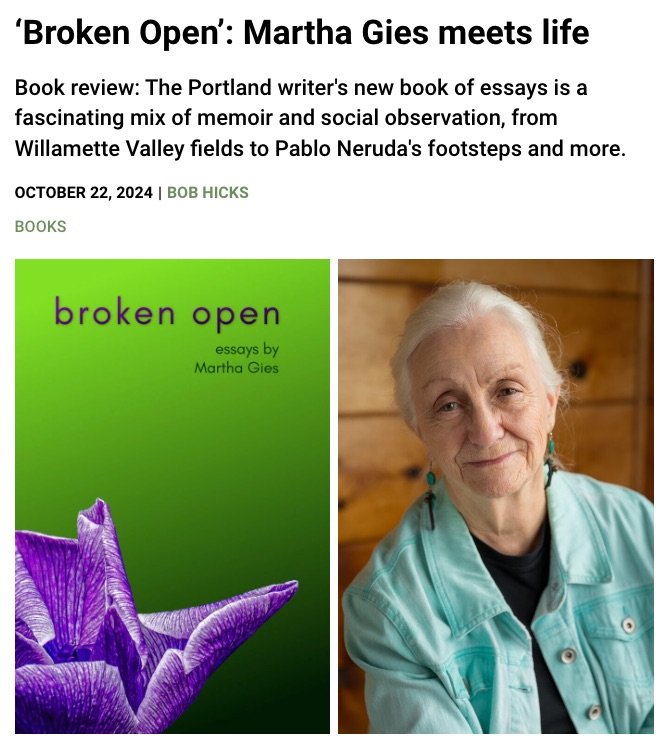

“Broken Open”: Martha Gies meets life

by October 22, 2024, Bob Hicks

Article also on Oregon Arts Watch website here

“A boyfriend once planted me in a Massachusetts commune, where I lived for two months as our relationship unraveled,” Martha Gies writes in her new collection of essays Broken Open. “There the girls grew vegetables, chopped wood for the stove, baked bread, and cooked the meals, while the boys smoked weed on the front porch and then loitered with visible impatience around the kitchen door. When the summer of 1973 ended, I flew to Oregon.”

Well, the 1960s and ’70s were like that. And for Gies, who grew up on a farm in the Willamette Valley near the town of Independence, it was a flight back home. She soon found herself in Salem, where she took a job driving a taxi on the night shift, seeing the town and the people in it from the bottom up.

She quit that job, and soon enough she was on the road again:

“Right after Christmas I joined a stage magician and his wife, Miss Nevada World. My job, which required me to dress like a showgirl, was to be cut in half in high-school auditoriums from Butte to Nogales.” Somewhere in Arizona The Great Kramien abruptly fired her, and, close to broke, Gies headed back north.

It’s been that kind of life: settled, farmlike; restless, curious, searching, analyzing, on the move. Gies has lived in Seattle and Portland and beyond, spent time in Mexico and South America and elsewhere, worked with filmmakers and farmhands and prison inmates and homeless people and for a year as a deputy sheriff, and always written about what she’s seen and felt, including her previous book Up All Night, a series of profiles of Portlanders working graveyard shifts. She’s spent more than 30 years as a creative writing teacher. It’s been a life lived full-tilt and a life of contemplation: a life both lived and examined.

Broken Open — a collection of 18 essays, several published previously, several not — is a fascinating mixture of memoir, social observation, and literary journalism, with some spiritual searching and progressive politics and defending of outsiders and underclasses in the mix. It’s written in a clear clean rhythm that moves swiftly forward even as it plunges into surprising depths, providing pleasure in its style and its sometimes wry observations, and vicarious adventure in the stories she relates.

Gies seasons her essays with reflections on literary figures including John Steinbeck (whose The Grapes of Wrath “plunged me into a desperate concern for the poor” when she was 16); the novelist and essayist Nelson Algren; the Northwest short-story master Raymond Carver, with whom she studied (her essay Teacher: A Memoir of Raymond Carver is an insightful mini-study of the writer and the writing craft); and the great Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (whose boyhood journey from mountain town to ocean she retraced in 2000 and describes in the essay Where Pablo Neruda First Saw the Sea.)

For all of her rebel streak or just plain thirst for experience, Gies’s essays reflect a fragile balance between urban and rural values that many Northwesterners, perhaps especially those who’ve moved from smaller to larger places, will recognize. In a way, Broken Open puts some patches on the deep divide between Oregon’s farmlands and its cities, revealing how the values of each can overlap. Her concern for outsiders and those on the lower end of the economic scale stems at least in part from her friendships with the workers in her family’s hops and asparagus fields.

As she ages, her life takes a considered turn toward religion, but a religion of some activism and more than a little concern for those on the culture’s outside. The premature deaths of her father, a successful lawyer, and her younger sister played a role in her evolving beliefs.

Gies’s essay A Father’s Story links in intriguing ways to her evolving belief in a religion rooted in social justice. First published in Portland Monthly magazine in 2005, it provides a fascinating look into the life of Kent Ford and the politics of a nation bound on rooting out and punishing what is sometimes called “the enemy within,” whether it is actually an enemy or not. Ford had founded the Portland chapter of the Black Panther movement, led it for a decade, among other things providing food and care for those who needed it, and is still a potent figure in the city’s quest for basic rights. Gies’s essay begins with the Bush II Administration’s 2002 “war on terrorism” and the arrests of four people who were part of what became known as “The Portland Seven.” One of them was Kent Ford’s son, Patrice Lumumba Ford, who despite scant-to-no evidence of wrongdoing and increasing skepticism about “the ethics of these FBI-concocted sting operations,” was incarcerated until 2018. “I overheard a chilling remark,” Gies writes: “‘They could never get Kent Ford, so they finally got his son.'”

Through it all, Gies’s childhood remains with her. In the book’s final essay, on the vagaries of memory, she reflects: “Now, in my Portland bedroom, where a quiet avenue runs beneath second-story windows, I sometimes wake with the sensation that I am back in the bed of my childhood, and I expect the next set of headlights to reveal those corner fountains and flowering terracotta pots that I have not seen in fifty years.”

Best, then, to write it all down, while you can.

——————————————————————-

About Bob Hicks

Bob Hicks has been covering arts and culture in the Pacific Northwest since 1978, including 25 years at The Oregonian. Among his art books are Kazuyuki Ohtsu; James B. Thompson: Fragments in Time; and Beth Van Hoesen: Fauna and Flora. His work has appeared in American Theatre, Biblio, Professional Artist, Northwest Passage, Art Scatter, and elsewhere. He also writes the daily art-history series "Today I Am."